Trauma Early Recognition and Sensitivity Make All the Difference

An interview with Prof. Danny Horesh from the Dangoor Center and the Department of Psychology at Bar-Ilan University on risk factors and resilience in the face of traumatic stress

“What trauma does, in all its forms, is deliver a kind of karate blow. It leaves people feeling that they are no longer the same person they were before, or after, the impact, something we all recognize from the events of October 7.” This is how Prof. Danny Horesh of the Dangoor Center for Personalized Medicine, head of the clinical track and director of the Trauma and Stress Research Lab at Bar-Ilan University, describes the common thread shared by trauma survivors of every kind.

Alongside his clinical research, Prof. Horesh works directly with a wide range of trauma-exposed populations, including combat soldiers, former hostages, women who have experienced pregnancy loss, and others, while also developing integrative treatment approaches. His close, ongoing contact with patients, together with the data emerging from our collective trauma on October 7 and the multi-front war that followed, has provided distinctive and valuable insights.

What turns a difficult experience into trauma? Why can the same event become traumatic for one person but not for another?

“That’s probably the biggest question in trauma science,” he says. “We are trying to understand why two soldiers in the same armored vehicle, who were objectively exposed to the very same attack, can go on to develop completely different psychological responses, both in type and in severity. That is what the entire field of trauma research is trying to unravel, at the emotional, cognitive, behavioral, biological, and genetic levels.

“Broadly speaking, it comes down to a combination of personal factors that existed before the trauma and the kinds of traumatic experiences the person has faced in the past: the degree of exposure, how graphic what they saw was, how much they dissociated during the event, and many other factors related to what happened afterward.

“One factor that comes up in almost every study is the presence or absence of social, spousal, and family support. When it comes to trauma, it really is ‘not good for a person to be alone.’ Loneliness is a significant risk factor; conversely, support that is attuned to the individual’s needs is critically important.

“Another major factor is meaning-making: after the trauma, is the person able to derive some form of meaning from what happened? Can they understand the experience within the broader fabric of their life, within their personal narrative? Those who succeed in shaping a meaningful personal story out of the trauma, whether on a faith-based level, an ideological level, or as a sense of personal mission, tend to navigate the post-traumatic journey better than those for whom the trauma remains meaningless and frozen in time.

“How a person understands the event on a cognitive level also matters a lot. Do they see what happened as something internal, telling themselves ‘this is my fault,’ or as something external, a kind of force majeure beyond their control? We aim to turn these insights into genuinely personalized interventions. We are not there yet, unfortunately, and it is a process that will take a long time.”

“My radar has gotten so used to detecting danger that I can feel that I’m really not the same person anymore.”

“My radar has gotten so used to detecting danger that I can feel that I’m really not the same person anymore.”

How Trauma Disrupts Personal Identity

You‘ve studied populations that are very different from each other: captive soldiers, women who have experienced pregnancy loss, and people with autism. Do you see shared patterns?

“Yes, absolutely. At the end of the day, a person is a person, and trauma is trauma. Regardless of the circumstances, trauma has common features: loss of control, a sense of helplessness, dissociation, and psychological disconnection.

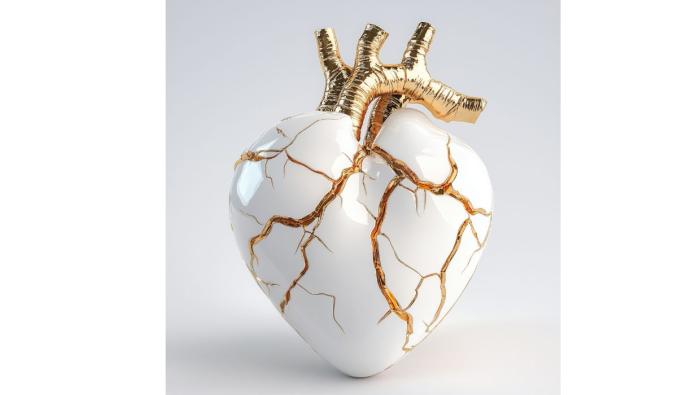

“But the one thing that is most shared across all the populations I have studied, and all the patients I have treated, is the experience of a clear ‘before’ and ‘after.’ ‘I am not the same person I was before and after the trauma.’ A traumatic event creates a kind of watershed, and it becomes very difficult for a person to integrate who they were before with who they are afterward. We have all seen this since the disaster of October 7. For many of us, it is hard to even remember life on October 6; it feels like a different world. For someone who is actually experiencing PTSD, this split between before and after tends to be much more extreme. In therapy, we go through a process of trying to stitch those parts back together and create some form of integration.”

Could you give a concrete example from our own lives?

“One thing we as a society need to understand better is that soldiers, men and women, who are now returning after dozens or even hundreds of days of service in Gaza are going through a process of reintegration into civilian life. Even though the geographic distance between here and Gaza is short, the psychological distance is enormous in every sense.

“This reintegration is extremely difficult for a student returning to campus or for a software engineer going back to a high-tech job. Simply stepping onto civilian ground again, suddenly walking on the sidewalk near their home, taking the dog out, sitting down at a computer, can feel like something they are completely disconnected from. On a physical and human level, it can feel utterly alien. Even at the sensory level: what am I used to hearing, seeing, smelling? How alert am I? What is my thinking speed? My internal radar has been trained to detect danger to such an extent that I can feel like I’m no longer the same person at all.

“And it doesn’t stop there. At the family level, too: what do I suddenly do with the baby who was born while I was away, with a child’s tantrum? Sitting in the living room at eight in the evening, is it quiet outside? What is this quiet? The quiet feels suspicious.

“All of this can show up on a symptomatic level, but also on a deeply identity-based level, an experience that says, ‘This is not me, and I don’t belong here. My place is not here, even though it was exactly here just a few months ago. As a society, we don’t always grasp how absolute and overwhelming this experience can be.”

Not Walking on Eggshells

What can we, as a society, do to help?

“Two things matter most. First, the experience of validation. There is often a feeling that ‘an outsider can’t understand,’ so it’s important to help the person feel that someone who wasn’t there can, in fact, understand. To acknowledge that it was very hard, that it is hard right now to sit in a classroom or in front of a computer. That sense of validation is extremely important.

“The second thing is not being afraid to talk about it. Our natural response, as those around them, is often excessive caution, as if we need to walk on eggshells around the event. That is one of the biggest mistakes, because it can reinforce the feeling that there’s some kind of bomb inside the person that must not be touched. It deepens their sense of loneliness. As people close to them, we want to make it clear that if they want to talk, there is space for that, that we aren’t afraid to ask where they are holding today, and that this, too, is something we can accept.”

Why is this so important?

“What drives post-trauma is avoidance. It is the number one enemy. There is a very strong and very natural tendency to avoid touching it, talking about it, even thinking about it. It is very easy to reach a point where everyone collaborates with that avoidance, as if it is contagious. No one talks about the traumatic experience; no one goes near it. But in truth, what avoidance brings with it is far more frightening. We know this from clinical work, from research, and from life itself.”

Even though it looks like the war is winding down, that doesn’t mean it’s truly over.

Even though it looks like the war is winding down, that doesn’t mean it’s truly over.

What do the latest studies show about the situation in Israel?

“In Israel, more and more data are coming in. Studies conducted at different stages of the war show significant rates of post-traumatic symptoms, PTSD, depression, and anxiety. That is not surprising. This is a very unique situation, with so many overlapping circles of trauma, an exceptional combination of symptoms at the level of the general population.

“And even if it seems as though the war is winding down, that doesn’t mean it’s actually over, certainly not from a psychological standpoint. Post-trauma follows a very winding path over time. It is not a still photograph. It is a condition that responds to triggers, to reality, to the news, and even memory itself can ebb and flow.

“Additional waves of post-traumatic distress will continue to emerge, perhaps especially at this stage. The ‘after the war’ phase has arrived. People are coming home, and for some, the mental dust is settling, and the realization of what happened is sinking in. There will be groups who may have suffered less before and will struggle more now. There will be others who suffered greatly and will begin to recover. But it’s not a linear process.”

Ongoing Trauma and Secondary Trauma

What is multi-layered trauma?

“When someone is in a car accident, the trauma is focused and one-time. What we’ve experienced is a truly historic example of multi-layered trauma. There was October 7 itself and what happened on that day, followed by 72 hours of an ongoing event that already contained multiple traumatic moments within it. Then came a prolonged war. There is also chronic, ongoing trauma, such as being displaced from one’s home.

“It’s like a set of nesting dolls. Evacuees from the Gaza border communities, Nova festival survivors, evacuees from the north, hostages and their families, reservists, the casualties, and the wounded. And then there is Iran and the missile attacks. Even the trauma of the Gaza border communities alone is a form of community-wide trauma, in which entire communities were attacked, something that is very rare.

“At the same time, there are age-related dimensions: what children experience versus adolescents, adults, or the elderly. There are many intersecting and distinct layers here, and we are truly living through an event of historic scale.”

Tell us about the family trauma cycle.

“One of the phenomena we study in the lab is secondary traumatization, trauma circles that expand to include people who were not directly there: family members, children, caregivers, journalists, and others. We see that post-traumatic symptoms can quite literally spill over from one person to another within a family, between partners, or across generations.”

Can you give an example?

“An Israeli soldier who fought in the Golan returns home in significant distress. He sometimes wakes up at night screaming from nightmares. He avoids going anywhere near the north and rarely leaves the house. If the news is on, he can erupt.

“His partner and children live with this day after day for months. Gradually, the partner also starts waking up at night from nightmares. Suddenly, she dreams that she is fighting in the Golan. She was never there, but she has absorbed his experience so deeply that she now identifies with it. Her friends want to take her to a birthday celebration in the north, and she says, ‘Thank you, but not the north.’ She, too, has developed avoidance. The children don’t want to invite their friends over. All of a sudden, we see symptoms emerging. Family members are positioning themselves, on an identificatory level, inside his trauma. They respond to it and, without being aware of it, begin to experience it as their own.”

Prof. Danny Horesh: “The most significant factor is proximity-distance relationships that aren’t sufficiently regulated.”

Prof. Danny Horesh: “The most significant factor is proximity-distance relationships that aren’t sufficiently regulated.”

How can this be prevented?

“The most significant factor is poorly regulated closeness and distance in relationships. As family members, we very much want to be empathetic, but sometimes we sink into what I call empathic mud and slide into over-identification. It becomes hard to tell what is mine and what is not. At times, I so badly want to take away their pain that I stop thinking about myself and fail to regulate how much I enter into and step back from that empathy.

“The guiding principles are awareness and avoiding a rescue fantasy. You can help, but there are limits. You are not the savior. Practice self-compassion toward yourself. At the end of the day, do something for yourself, get some air, detox your mind. Do not feel guilty. Take time for yourself and recharge. We conducted a study on self-compassion among partners, and we clearly see that those who were better able to be forgiving and gentle with themselves were also better able to be empathetic, without becoming post-traumatically affected themselves.”

Evidence-Based Treatment Approaches

Which treatments have actually been proven to work?

“The field of PTSD treatment has developed enormously over the past three decades. There are three main evidence-based approaches.

“In exposure-based therapies, the patient is repeatedly exposed, both in imagination and in real life, to trauma-related stimuli. The goal is to make these triggers less reactive, to create habituation. This is an anti-avoidance form of treatment.

“Cognitive therapy, CBT, works continuously on distorted beliefs: that the world is dangerous, that no one can be trusted, that I am to blame, that I should feel shame.

EMDR is a method that primarily uses bilateral eye movements, which activate different parts of the brain and allow traumatic memories to be reprocessed through a mechanism similar to REM sleep.

“The goal of all of these approaches is the same: to reach a point where you realize that the traumatic story is not as threatening as you once thought. Anyone who recognizes themselves as suffering from post-traumatic symptoms should seek treatment from therapists who specialize in PTSD, ideally using at least one of these approaches.”

There is an interesting phenomenon known as “post-traumatic growth.” Do people come out stronger?

“Many people emerge from trauma with a sense that they have gained something, at the level of meaning. Viktor Frankl observed among Auschwitz survivors that those who had a narrative, an understanding of what the experience meant for them personally, were able to endure. You learn something new about your inner strengths, about relationships, about intimacy. Sometimes it is something spiritual or faith-based.

“One of the intriguing findings in research is that post-traumatic growth is often found specifically among people experiencing significant distress. Those with more post-traumatic symptoms also tend to report more growth. Why? Much like Frankl suggested, the idea is that sometimes you have to reach the bottom, a very difficult place within yourself, the bedrock of existence, in order to encounter a point where, if you do not discover something new about yourself, you simply will not survive.”

Trauma Among Caregivers and Journalists

A generation of children is growing up surrounded by trauma. What do you expect from them?

“As a father of children who have grown up over these past five years, I am not yet sure we truly understand what this generation has absorbed from this continuous sequence of traumas. As parents, we need to remember that this is not normal. I insist on that, it is not. And we must not give them the feeling that this reality is somehow normal or acceptable. It is important that they see that we recognize how hard it is to grow up this way.

“At the same time, there are very impressive expressions of resilience here. This is a generation that has grown up in extremely challenging years and still managed to study on Zoom and then off Zoom, take matriculation exams, live through a war, and maintain social circles. We also know that children have something elastic about them, strong life forces; they are slow to lose hope. What the broader processes will be is something we will only understand later. It will be fascinating to see how they remember this period when they themselves become parents.”

Prof. Horesh shares that he returned to Israel after a postdoctoral fellowship in New York and chose to join Bar-Ilan University because of its outstanding clinical program and the central role trauma plays in the university’s research. “I knew that Bar-Ilan has some of the country’s leading trauma researchers, and I wanted to be in an institution that offers real opportunities for collaboration,” he explains.

There’s no need to panic, but we do need to identify it, be open about it, and call it by its name.

There’s no need to panic, but we do need to identify it, be open about it, and call it by its name.

Over the past decade, he has collaborated with Prof. Rachel Dekel of the Dangoor Center in studies on trauma and family, examining couples of combat soldiers and their partners in Israel and the United States, and leading a therapeutic project on couple-based treatment for PTSD. Together with Prof. Ilanit Hasson-Ohayon, he conducted a multinational study funded by the Dangoor Center for Personalized Medicine on post-traumatic responses during the COVID-19 pandemic across five countries. He is also set to publish a forthcoming study comparing secondary traumatization among caregivers and journalists following the events of October 7.

What is the most important message you would like to share with the public?

“Trauma has tremendous power, and the most important thing is to be sensitive to its consequences and to recognize them in time. Whether it is you, a neighbor, a partner, a child, or a friend who has returned from reserve duty. There is no need to panic, but there is a need to notice, to keep an open mind, and to call it by its name.

“In psychology, we say that avoidance is a perpetuating factor; it pours oil on the fire of trauma and causes it to spread. Trauma is meant to be recognized early, given words, named, and acknowledged. Sometimes that alone already helps. But for some people it doesn’t, and that is where our responsibility comes in: to notice when signs of distress are intensifying, to talk, to offer help, and to help the person access good treatment.

“Right now, at a time when hostages have returned, and it may seem that the sounds of war are quieter, it’s important not to become complacent. There are still many people whose suffering is very deep. Recognizing it and talking about it is the most important thing. Not avoiding it, neither on a personal level nor on a social and community level.”

Last Updated Date : 08/02/2026