There are no bad bacteria, only bacteria in bad situations – Interview with Prof. Omry Koren

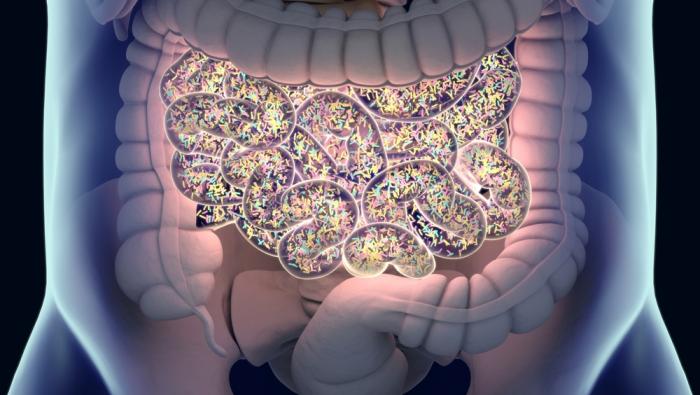

When Prof. Omry Koren was in the advanced stages of his PhD in microbiology, his oldest son was born. While he had been researching bacterial populations in healthy and diseased sea corals, the first few months of his son's life peaked his interest in the importance of bacteria in the early life of humans.

Today, Prof. Koren's lab focuses on the importance of gut microbiome bacteria in the first thousand days of a person's life. This year, he was listed as one of the most cited researchers in the scientific world for the sixth consecutive time. In addition, he serves as the Vice Dean for Development and Resource Recruitment at Bar-Ilan University and is one of the founders of an innovative start-up in personalized medicine.

We spoke with Prof. Koren to hear about his fascinating research and to collect tips on how to do so many things simultaneously- and excel in all of them.

The Dilemma Dividing the Microbiome Research Community

Since the days of Aristotle, philosophers have asked whether we are born a “tabula rasa,” a blank slate, or if the learning process begins before birth, in the womb. Until recently, researchers in the microbiome field have faced a similar dilemma.

Prof. Koren, is it true there is a controversy about when the fetus or baby’s body is colonized by bacteria?

“Until recently, this was indeed a significant dilemma in the field. This year a massive study involving dozens of researchers from different universities worldwide was published in which we concluded that a healthy baby first encounters bacteria during the passage through the birth canal and the womb. Most of the evidence we currently have indicates that the womb is a sterile environment, although some studies claim otherwise.”

So, bacteria do not affect the fetus until birth?

“Actually, they do, but the ones affecting it are the mother's gut bacteria. We know that the substances these bacteria secrete can pass through the placental barrier. They reach the fetus and influence its immune system and brain development. In other words, the fetus does not encounter the bacteria themselves, only the substances secreted by the mother's bacteria.”

How do you research the impact of maternal bacteria on the fetus?

“We conducted experiments on pregnant mice. When we gave antibiotics to one group of mice and compared it to another group that did not receive antibiotics, we saw that the activity of the gut bacteria changed, affecting fetal development. These experiments prove that the activity of the mother's gut bacteria impacts the fetus's development.”

And what about humans?

“We are researching the impact of antibiotics on gut bacteria in infants after birth. In experiments, we saw that at six years old, there are growth differences in boys who received antibiotics in the first week of life compared to those who did not. In other words, administering antibiotics in the early stages of life causes a change in the composition of bacteria that develops afterward, affecting growth.”

Is there such a thing as a gut feeling? The brain-gut axis

In recent years, Prof. Koren has been delving into a novel concept still in its infancy (but rapidly gaining popularity) called the “brain-gut axis.” Sounds strange? That's why we asked!

What is the “brain-gut axis”? Are the brain and gut connected?

“Absolutely. There are various communication pathways between the brain and the gut, such as the vagus nerve, which exits directly from the brain and creates a network of fibers interfacing with the nervous system and internal organs like the heart, lungs and the digestive system.”

Where do bacteria come into the picture?

“Bacteria produce various substances that bind to receptors in the digestive system, like serotonin, for example, and then a signal is sent to the brain via the vagus nerve. Among other things, serotonin affects our emotions, so our gut bacteria actually can influence our behavior- for instance, aggression levels.”

What happens in the gut affects aggressive behavior?

“In animals models, yes. Recently, we had an interesting research collaboration with McMaster University in Canada on antibiotics during breastfeeding. We discovered differences between groups of nursing mice pups that received antibiotics and those that did not – they had different gut bacterial populations and different behaviors. This discovery led us to conduct a very large follow-up experiment, and we are waiting for the results to be published in a scientific journal soon.”

Can you give us a spoiler?

“We saw something very interesting. Sterile mice (we have the ability to grow mice without bacteria under special conditions) were more aggressive than regular mice, while sterile mice implanted with gut bacteria calmed down. We saw the same phenomenon in flies as well.”

And what about ADHD or anxiety?

“We are talking about a research field that is still in its infancy. Not much is known yet, and I foresee great potential, especially in the field of psychobiotics- the study of the use of bacteria for behavioral change. We recently received a grant from the European Union for research in this field.”

A Professor Who is Also a Start-Up Founder

We heard that you are also the founder of a start-up related to predicting pregnancy complications. Can you elaborate on that venture and the connection to gut bacteria?

“Take gestational diabetes, for example. Currently, gestational diabetes can only be detected in the third trimester. In studies we conducted on hundreds of women, we found that according to samples, we could predict who would develop gestational diabetes already in the first trimester. We are talking about predicting months before the current diagnosis.”

Why is it important to predict gestational diabetes so early?

“Gestational diabetes can be relatively easily treated through dietary changes, but at this stage of diagnosis, the woman has already developed gestational diabetes. She is now at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life, and her baby is also at risk of various complications. We aim to predict the development of gestational diabetes before it develops.”

What are you currently working on?

“Today, we are working on predicting additional pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia or preterm birth, in collaboration with Bar-Ilan's entrepreneurship company, Unbox.”

Man's best friend: The bacterium

In the 17th century, researchers first observed bacteria through a microscope. Those researchers developed theories about bacteria as agents of disease, and the concept stuck. However, a few years ago, the microbiome field burst into our lives and changed our perspective on bacteria.

How has our understanding of bacteria changed?

“After hundreds of years of bacteria being perceived negatively, we began to understand that bacteria are not inherently bad, or at least most are not. Bacteria do not act alone; they are part of a community. Therefore, we need to look at the entire bacterial population and its relationship with the environment, whether that is a river, the soil- or an animal's body. Essentially, bacteria do not want us to be sick; we are quite a convenient host for them. We provide them with everything they need, and in return, they help us, but when this status quo is disrupted, they start behaving differently.”

Why has this field only emerged over the past twenty years?

“Because technology has advanced significantly. The microbiome field relies on technologies developed for the Human Genome Project, like genetic sequencing and all the omics technologies, which are a collection of technologies that give us a complete set of information about a certain element in the cell: genes, proteins, lipids, metabolites and more. This is why we collaborate with people like Prof. Yoram Louzon from the Mathematics Department, who is my partner in all my research. We also collaborate with Prof. Suleiman Khatib from the MIGAL Galilee Research Institute to study metabolites (substances secreted by gut bacteria). We also have collaborations with Prof. Nisan Issachar from the Faculty of Life Sciences, and with other researchers from the Dangoor Center for Personalized Medicine. The secret to success in these major research projects is collaboration.”

In conclusion, can you give us a tip on how to become the most cited researcher in your field, act as the Vice Dean for Development and Resource Recruitment at the university and manage a lab and students- all at the same time?

“The main tip is to love what you do. Today, for example, I am researching with Prof. Nisan Issachar how the type of birth- natural, cesarean section, or home birth- affects the newborn's gut bacteria. If you think about it, it was the birth of my first son by cesarean section that inspired me to transition to microbiome research. Strive to research what you love, and be curious and interested in everything.”

Last Updated Date : 12/11/2024